Swiss cheeses and the formation of eyes

- | آتاماد |

- Viewer: 453

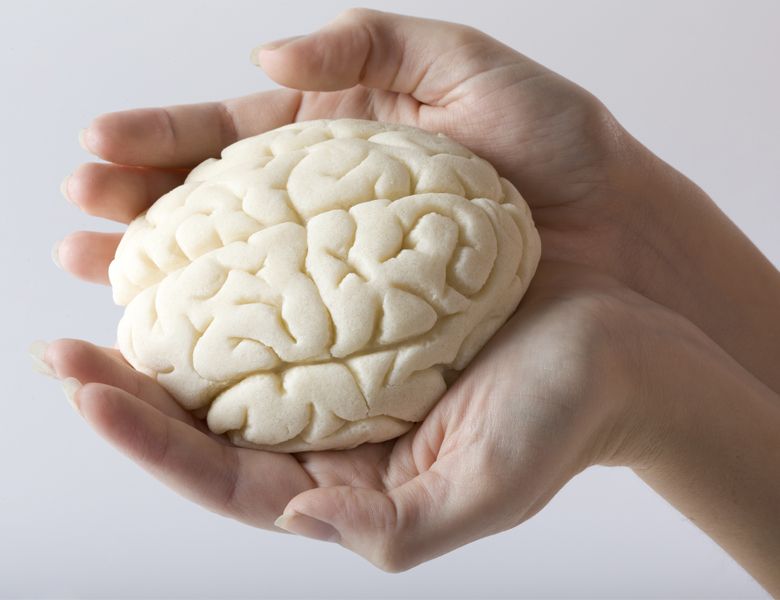

The phenomenon of the formation of eyes in cheese has attracted the attention of scientists since the beginning of cheese research. The scientists' research in 1971 about the formation of eyes in Emmental cheese shows that there were very precise ideas about the formation of eyes in cheese at the beginning of the last century. First of all, it is necessary to mention the difference between eyes and mechanical holes in different types of cheeses.

The difference between mechanical openings and eyes in cheese

Many have difficulty distinguishing between "mechanical holes" and "eyes". Some cheeses, such as Colby, have small jagged openings in their texture. These are called mechanical holes and are related to the way the cheese curd is compressed, and they are not gas holes (Figure 1).

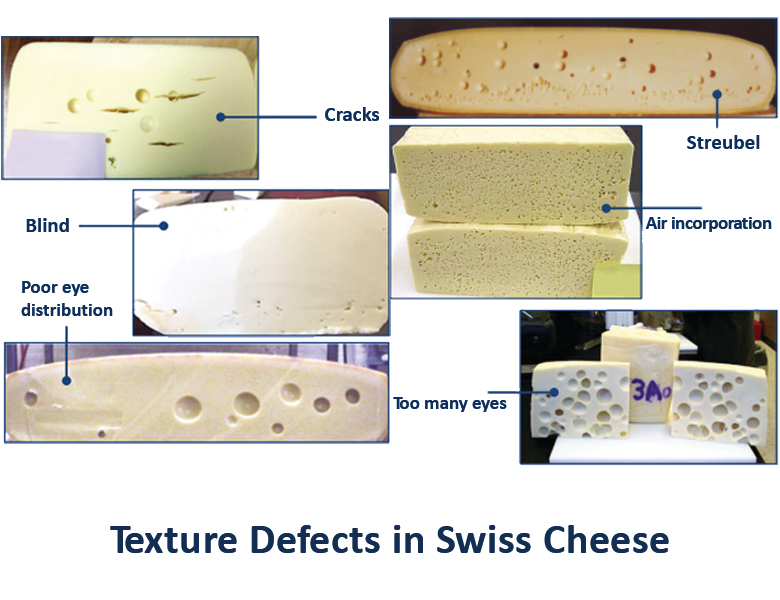

The formation of eyes due to the production of gas is the main sign of the quality of Swiss-type cheeses. The characteristics of the holes (the nature, size, and number of gas holes) are related to the typical characteristics of any type of cheese. The holes are usually round and shiny. The size of the eyes varies widely, from large (diameter 1-3 cm) to small (diameter 0.5-1 cm), and the number and space between the eyes in the block cheese depends on the type of cheese. Emmental, the most well-known Swiss cheese, has many large eyes, Gruyere has smaller eyes, while Beaufort usually has no eyes (blind).

Eyes formation related to CO2 production is a desirable feature in Emmental and other Swiss-type cheeses, but gas formation is also a defect in many types of cheese. CO2 production is the final product of propionic fermentation. But it can also be caused by the activity of unfavorable gas-producing microflora, such as coliforms, yeasts, or clostridium. The formation of holes or blowing defects in cheese is due to the production of undesirable gas that is often associated with off-flavors, for example, hydrogen from the unfavorable fermentation of butyric acid by Clostridium thyrobutyricum.

The formation of eyes in Swiss cheese is determined by the production of CO2 and the creation of holes and growth in the protein matrix with suitable mechanical, physical, an chemical properties. The cohesion, elongation viscosity, and fracture properties of Swiss cheese, which creates a soft and elastic texture, play a major role in the formation of holes. Eyes formation is a dynamic process that is related to textural changes during ripening and also to gradient phenomena (water, salt, enzyme activity) in the cheese block.

Eyes are caused by the production of gas, mainly CO2, from propionate lactate fermentation by bacteria during the ripening of Swiss-type cheeses. There are gases except CO2 in cheese that originate from residual air in the milk and remain during the cheesemaking process. Some hydrogen production can also help the cheese to form eyes.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Propionibacterium

The genus Propionibacterium consists of two distinct groups from different habitats: first, strains commonly found on human skin, known as the "acne group", and second, strains isolated from Milk and dairy products, which are called "dairy" or "classic". PAB strains of the lactic group of propionibacteria include four species, Propionibacterium freudenreichii spp., Propionibacterium acidipropionici, Propionibacterium jensenii, and Propionibacterium thoenii.

PAB was first isolated from Emmental cheese at the beginning of the 20th century by von Freudenreich and Orla-Jensen. They are present in raw milk in populations ranging from 5 to more than 105 CFU/ml.

Four dairy PAB species are found in raw milk, the most popular of which is P. freudenreichii. P. freudenreichii grows in Swiss-type cheese during the ripening period in a warm room (18-24°C) and reaches populations of 5 x 109 CFU/g of cheese. P. freudenreichii is the main species grown in Swiss-type cheese, while P. jensenii is the main species identified in Leerdammer cheese.

The use of PAB as a starter culture is widespread in the production of Swiss cheese. The level of PAB inoculation in milk varies from 103 to 106 CFU/ml of milk according to cheesemaking technology. In some Swiss-type cheeses such as Comt'e produced from raw milk, propionic fermentation is solely due to the indigenous PAB microflora present in the raw milk.

P. freudenreichii grows at warm temperatures during ripening and ferments lactate to CO2, acetate, and propionate. Many carbohydrates can be metabolized by P. freudenreichii, but lactate, produced by LAB, is the main carbon source for PAB in cheese.

Relationship between eye formation and taste development

Swiss-type cheeses have a typical taste that is described as sweet and nutty. The taste and the formation of the eyes both happen during the ripening period, but they are not directly related to each other. Firstly, if all the conditions (proper amount and level of gas formation, limitation of diffusion through the rind, suitable cheese texture) are not suitable for the formation of eyes, Swiss cheese flavor can form without the formation of eyes. Second, gas formation occurs mainly during ripening in a warm room, while flavoring compounds can be formed in different periods of cheese production and ripening. Thirdly, the formation of gas is mainly due to the activity of PAB in Swiss-type cheeses, while the formation of some flavor compounds can be caused by the activity of other bacteria in the cheese.

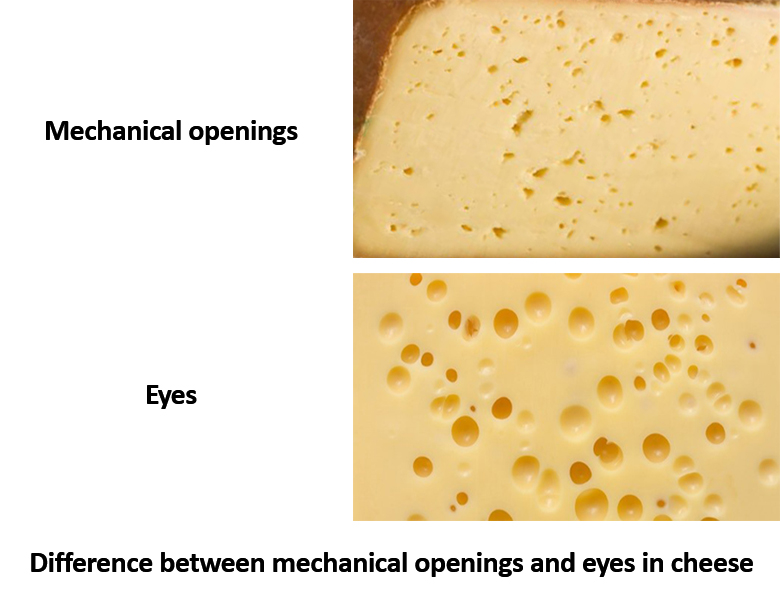

Texture defects in Swiss-type cheese

A proper understanding of CO2 production, its solubility, and diffusion in the cheese matrix is necessary to obtain the desired quality of cheese without cracks. Carbon dioxide in the cheese matrix is mainly produced due to lactate fermentation by propionic acid bacteria during ripening in a warm room. The speed and amount of CO2 production are influenced by factors such as propionic acid bacteria strains, ripening temperature, and cheese composition. The rate of CO2 production in semi-hard cheese has been determined to be 10-15 mmol/kg per day at constant temperature (25°C) and salt-to-moisture ratio (2% w/w). Carbon dioxide dissolves in the oil and water phases of cheese. However, its solubility is highly temperature dependent, i.e., the solubility of CO2 in the lipid phase is lower at low temperatures (4°C) than at high temperatures (20°C). The opposite is true for the solubility of CO2 in water. Therefore, any change in ripening conditions or cheese composition or both can change the solubility of CO2 in the cheese matrix, which in turn can affect the internal pressure of the cheese. Controlling the internal pressure of the cheese is essential, as excessive pressure can lead to cracks that are unattractive to consumers. In addition, these cheeses can produce many broken pieces during size reduction operations, such as cutting and slicing, which results in a loss of profit for producers.

On the other hand, if the gas pressure is insufficient, small or no holes (blind cheese) are formed. The absence of eyes in Swiss-type cheese may sometimes be due to the inability of Propionibacteria to grow and produce CO2 in sufficient amounts. Residual antibiotics in milk, high cooking temperature, an increase of copper content in milk through storage in inappropriate containers, and incomplete production of lactic acid in milk and curd due to bacteriophages against starters are other factors involved in this defect. Also, some heterofermentative starter cultures can also disrupt the formation of the eyes by inhibiting propionibacterium.

In general, factors that affect the size, distribution, and quantity of eyes in Swiss-type cheese include the pressing time, the amount of time the cheese spends in the warm room, lack of pre-drawing whey into the press, and salt levels. If too much air is incorporated into the cheesemaking process, it results in nesting or Streubel defects. Blowing defects in Swiss cheese also occur early or late in the ripening process. Early blowing can occur due to too high warm room temperature is, or the presence of coliform bacteria. Late blowing is usually caused by anaerobic spore-formers like Clostridia tyrobutyricum about 2-3 months after production, and for this purpose, not many spores are needed, only 5 spores per ml are enough to cause this defect (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

So, eye formation requires gas production at both a high rate and a minimum level. The production of 1 liter of CO2 per day in a 75 kg block of Emmental cheese with rind at a temperature of 23°C (warm room) does not cause eye formation because the formation of eyes occurs when the amount of CO2 production in the cheese is more than 2 liters/day.

In addition to the production of CO2, other gases can also be formed in cheese. For example, the production of hydrogen (H2) results from the growth of some undesirable Clostridium species that ferment lactic acid into butyric acid, acetic acid, CO2, and H2. The high efficiency of H2 production and its low solubility in water lead to blowing defects. Improving the sanitary conditions of milk production, removing spores with microfiltration, and bactofugation of milk helps to prevent blowing defects. Ammonia gas (NH3) may also form from the deamination of amino acids, but this phenomenon has not been reported for Swiss-type cheeses.

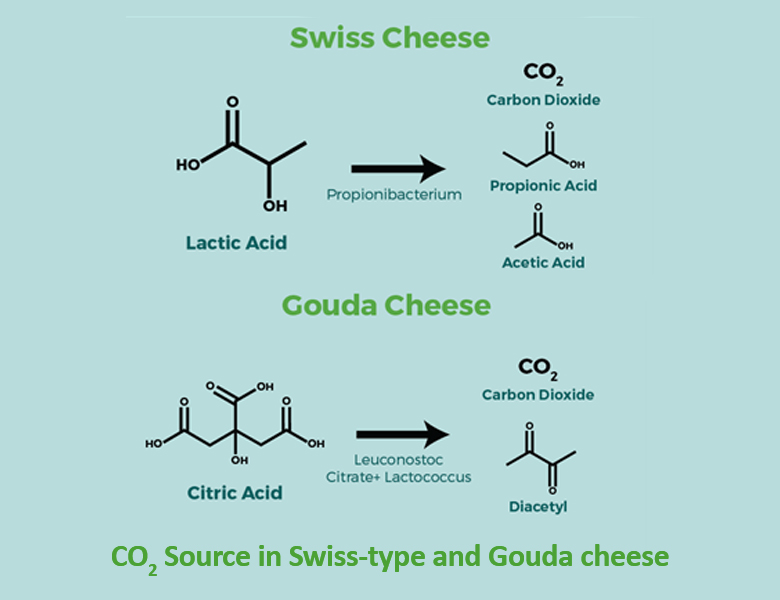

The difference in the origin of CO2 in Swiss-type and Gouda cheese

Eyes in Swiss-type cheese are formed due to the breakdown of lactic acid (which is produced by the starter cultures from metabolizing lactose) by Propionibacterium. Then the propionibacterium metabolizes the lactic acid into CO2, acetic acid, and propionic acid. But in Gouda cheese, eyes formation is due to the breakdown of citric acid. Bacteria such as certain species of Leuconostoc or Lactococcus metabolize citric acid into CO2, diacetyl, and other compounds. Due to the low amounts of citric acid in milk, the growth of the rind in Gouda cheese is very limited (Figure 3).

All in all, Swiss-type cheese is one of the most challenging cheeses to produce. However, this unique cheese is appealing to consumers because of its taste, flavor, and nutritional value.

Figure 3.

References:

https://www.cheesescience.org/eyes.html

Law, B.A. and Tamime, A.Y. eds., 2011. Technology of cheesemaking. John Wiley & Sons.

https://www.cdr.wisc.edu

GET IN TOUCH

Copyright © 2023 Atamad.com All right reserved

Website design and SEO services by Seohama team – Web hosting by Sarverhama

Copyright © 2023 Atamad.com All right reserved

Website design and SEO services by Seohama team – Web hosting by Sarverhama